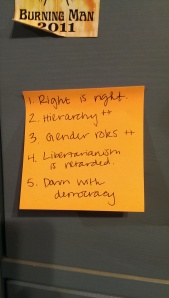

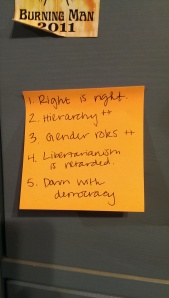

I wrote this note to myself a couple of weeks ago. It has been posted by my desk at home for consideration.

So I’m not entirely sure how useful this particular post will be to anyone else, but it’s important that I write it regardless, seeing as how I find myself in an uncomfortable position lately with respect to my politics and even my worldview in general (a little more background is here if you want it). At least a couple of neoreactionaries have found me interesting to talk to in this capacity, because I am intelligent and still somewhat of an outsider to the movement, albeit a largely sympathetic one who’s becoming better informed by the day.

I got interested in NR shortly before the TechCrunch piece dropped, then there was the Vocativ thing, and I understand those were ok by mainstream media standards, but I’d rather take something written by a reactionary, for (neo)reactionaries, as a starting place for analyzing where I stand at present. Pretty sure that there has to be at least some controversy surrounding Michael Anissimov’s “Premises of Reactionary Thought,” but as far as I can tell it’s a fine place to begin. Having now dabbled in NR reading and NR twitter, here’s my status on each of the 5 basic criteria of reactionary thought that Anissimov offers:

1. Right is right.

Well, this is hard for me to stomach, because I have spent my whole life running in circles that pride themselves on being “liberal” and, through all my political wanderings, have never self-identified as departing liberal land in any important way. Of course, “liberal” and “conservative” used colloquially in the U.S. have particular connotations and extensions on the political scene as it is and it’s kinda screwed up. I do realize that “right” and “left” in this semi-technical sense have much more to do social order and disorder, respectively, than they have to with political parties or platforms or particular policy issues or whatever.

“Order” and “disorder” are a little loaded, though. I mean, who likes disorder? I can definitely pass the ideological Turing test for modern liberals, and I’m sure that people on the left would prefer to draw the distinction between something like social “stasis” and “dynamism.” That makes the disorder option sound better, doesn’t it?

I do understand that social disorder or dynamism or change is costly, often in ways that go largely unnoticed until it’s too late, and I have been taking more seriously than ever before the idea that social change is to be regarded mostly with suspicion and not dreamy-eyed optimism. So I guess, much to my own chagrin, that I’m basically on board with “right is right.” I need to sort out what “liberalism” still means to me, if anything. And I retain doubts that all forms of social disorder/disruption are to be avoided (or would have been better off being avoided); might say more about this at some point. However it’s possible that the rhetoric about order and disorder is just simplified, though, and that to attack that position would be strawmanning anyways. You guys can help me with this later.

2. Hierarchy is basically a good idea.

I was essentially in agreement with this principle even before stumbling upon NR, truth be told. I have long been deeply, deeply skeptical of liberal calls to equalize respect for persons, as by socially engineering jobs and familial arrangements and incomes. It’s one thing to try to raise the level of material well-being of the least well-off for humanitarian reasons, because they are suffering right now. But a substantial component of the well-being of some social creatures – e.g. primates, humans – originates in status itself, a positional good which cannot even in theory be distributed equally.

There’s something a little misleading about even speaking about hierarchy as being a “good idea.” It’s no one’s idea at all, and this is part of what the critics of hierarchy miss, thinking of it as they do as some conspiracy hatched by the powerful to form and protect a tiny class of elites. No one dreamed up hierarchy as a way of deliberately organizing human societies. It emerged due to a variety of biological, historical, cultural, and other factors, and continuously re-emerges in response to changes in the relevant factors. Attempts to remove or “flatten” hierarchy from the top down only twist it past the point of being useful or productive or meaningfully organizing at all.

This is not to say that hierarchy marks every social group in the same way – sometimes companies, under special conditions, are able to voluntarily and conscientiously flatten their organizational structures with some success. And of course, we can admit that hierarchy is basically a good idea without necessarily endorsing all particular features of the hierarchies existing writ large in society today. E.g., to the extent that hierarchies have developed in response to shitty government policies that reward rent-seeking behavior, they are morally on shaky ground. The problem is not that these policies allowed some hierarchy at all to develop. The problem is that they encouraged the formation of a particular hierarchy that’s not beneficial to society and to individuals in the right way, a hierarchy that rewards some of the undeserving at the direct expense of others. Proper hierarchies, on the other hand, are positive-sum with fair (though not necessarily equal) distribution of gains, and are morally unproblematic for that reason.

3. Traditional sex roles are basically a good idea.

This phrase reads funny to my feminism-worn ears, I am tempted to re-write as “gender roles,” but no use in getting hung up over that. And, as re: hierarchy, I think it’s a little off again to describe sex roles as an “idea” at all. Rather, they are (or used to be…) an emergent feature of sexual dimorphism and gender-related comparative advantages.

Anyways, for various reasons, I find gender roles particularly fascinating at this point in my life. As a woman in my late 20s who has alternately enjoyed and endured a number of mediocre to bad relationships with men over the past 10 years (including a “starter marriage,”) it is becoming increasingly important to get some handle on which kinds of relationships work well, and why. Having grown up firmly embedded within the liberal, educated, upper middle class, I have been exposed to a melange of useless information and impressions about what I can or should do with myself, qua woman: you’re so smart, go to college, go to grad school, get any job you want, lean in, have it all, you don’t have to have kids!, but you’ll surely want to, staying home would bore you to death, but not staying home will make you feel guilty, men should want you for your brain not your body!, but [name], you’re so pretty, when you’re older you’ll break hearts. It’s enough to make your head spin.

I’m not ready to condemn feminism in general as a necessarily + universally backwards, socially destructive movement. But it’s hard to deny that it’s fucked some things up. And some of its effects have spun themselves into apparently self-reinforcing, destructive cycles: e.g., it’s good for any individual woman to realize that, were it necessary, she could work outside the home to support her kids. But then women start expecting less from even their allegedly provider husbands. Now even the potential husbands are crappier providers, and the women see little reason to marry them, even when they’ve birthed those men’s children. The men have little reason to marry the women, too – they’re going to be difficult and expensive to live with, and difficult and expensive to divorce. Who’s winning here? Women who end up working even when they don’t want to? Unmarried men who live in a perpetual state of adolescence and sociofinancial marginality? Married men who endure chronic and pernicious emasculation? Latchkey children with absentee fathers?

I have had it up to here with the false consciousness explanations of women’s preferences to stay home and raise children. Given everything we know about evolution and men vs. womens’ places in that process, the burden of proof – and it is a heavy one – lies squarely upon anyone who wishes to disprove that women are, in general, natural child-rearers: we simply would not be here if the mothers before us weren’t.

This does not entail that it is bad or wrong for individual men and women to opt out of the basic family arrangement. It does mean that large-scale attempts to shift it by various means will work well for a few people and poorly for most. Politically and socially influential people are mostly projecting their own preferences, motivations, and capacities onto the population in general when they recommend policy and attitudes regarding these topics.

Also I expect that this venue will occasionally devolve into sex blogging lite. Thanks for bearing with me, or cross your fingers for it, depending.

4. Libertarianism is retarded.

Ok, I’m not the PC police, but I would have worded this differently. Actually, this is probably the aspect of NR thought about which I will have the most to say, and not all today, either. I have been involved with the “liberty movement” (gag) for about 5 years and definitely go through cycles of feeling excited, correct, unsettled, jaded, discouraged, over it… lather, rinse, repeat.

Being very familiar with libertarian internet subculture, I can tell you that quite a few of the 20-something set are actual anarcho-capitalists. Also the “Bleeding Heart Libertarian” tradition is rapidly coming to the academic fore, or should I say re-emerging, because one of their points is that libertarianism’s (i.e., classical liberalism’s) heritage is fairly leftist, and only relatively recently has libertarian thought come to be associated with the right and crony capitalism and such. This libertarian association with the right has been uneasy, of course, and “fusionism” has served as a perennial topic of discussion between Beltway libertarian types (e.g., Cato, Reason) who probably split liberal/conservative at philosophical bottom and those libertarians and anarchists who would eschew political participation altogether (e.g., many agorists, Free Staters, seasteaders).

So it’s a diverse group, definitely populated partially by “retards,” and even moreso by men “on the [autism] spectrum.” The movement is definitely large enough to attract mere contrarians, nerd groupies, econ jargon parroters, token women seeking attention, and worse, and they are growing louder and louder online by the minute. This makes the intellectual tradition – and present – look worse than it is. It makes it look retarded.

Anissimov claims that libertarians, having taken personal freedom as axiomatic and therefore valuable at all costs, “refuse to consider the negative externalities of that freedom to traditional structures like society and the family.” I don’t think this is a fair charge; it is at most true of talk show/caricatured libertarianism. For a long time now, libertarians and anarchists (some of those identifying both with the left and with the right) have concerned themselves with the ways in which government has intentionally or unintentionally shaped society for the worse. Many libertarians of the past and the present emphasize – and criticize – the way in which taxation and government actions/regulations crowd out mutual aid activity, which is preferable both on moral grounds (because it is voluntary) and because it can be more targeted and effective in its methods than bloated, knowledge-problem-laden social services bureaucracy.

Further, consider these standard libertarian talking points: The war on drugs, especially combined with certain forms of welfare, have decimated the poor, especially black families in the inner city. Heavy-handed regulations that make it difficult to start businesses keep the poor and poorly-connected from life-improving entrepreneurship opportunities that could feed their families and employ their neighbors. Housing regulations setting high bars for the goodness of homes see to it that marginal renters are homeless instead of temporarily situated in densely-occupied and less-than-glamorous apartments. And let’s not forget the mortgage subsidies that encouraged families ill-suited for home ownership to assume subprime and no/low-down-payment mortgages for too much house. This resulted in recession-era neighborhood blight and social upset instead of suburban paradise for all. These are all points made routinely by libertarians, in an effort to show how government fucks up family and community.

Also notice that libertarians mostly really love meritocracy, and frown upon attempts to tamper with the natural way in which the talented and smart and hard-working rise to the top. This is part of a larger libertarian acceptance or endorsement of hierarchy in general – again, libertarians mostly only have problems with hierarchies that are government-enforced or government-disrupted (e.g., the political ruling class and its undeserved wealth saturating the suburbs of Washington D.C.). Even apart from meritocratic considerations, libertarians tend to reject government attempts to alter the hierarchies that would result from voluntarily transactions in the marketplace, and for that reason oppose legislation to enforce gender wage parity, to require preferential hiring of disadvantaged groups, to contract with or protect some kinds of businesses instead of others, and so on. If the market “sees” a difference between persons, then that is presumptive reason to let that difference be acted upon, even if there remain uncomfortable patterns in the way that persons tend to be treated when we compare group over group. These aspects at least superficially check out as consistent with broad NR thought, as far as I can tell.

The idea that libertarians all just want to “go Galt,” and the charge that “if a libertarian society would leave many out in the cold, libertarians seem not to care” are cliched stereotypes of only the crudest and most immature of libertarians. I expect more of Anissimov than to repeat these sound bytes uncritically. It’s fine to reject libertarianism for other reasons; I expect that the main reactionary criticisms are simply that libertarians simultaneously (1) over-value individual liberty in principle, and (2) expect better outcomes from enhanced individual liberty in practice than are reasonable to expect. Let’s discuss these principled and practical objections to libertarianism, vis-a-vis the reaction/neoreaction, here more in the future.

5. Democracy is irredeemably flawed and we need to do away with it.

Moving as I have been within libertarian circles for the past 5+ years, this point is not so new to me, and it doesn’t strike me as particularly heretical to suggest it, even if it’s way afield of the Overton window. I was close to fully espousing anti-democratism even within the context of my libertarianism prior to stumbling upon the neoreaction.

Libertarians are often pretty happy to bitch about democracy to anyone who’ll listen, but there’s no real consensus about what system to endorse instead. Economists, many/most of whom are tepidly libertarian or classically liberal, have helpful analyses of how democratic stuff operates in practice: public choicey things like logrolling, diffusion of costs/concentration of benefits as pertains to lobbying, the rationality of (un)informed voting, legislation as the advance auction of stolen goods so pithily described by Mencken, etc etc. Beltway libertarians, mostly minarchists of whatever stripe, will talk a nice game about constitutionally-limited government, but kinda fail at suggesting what e.g. America could have done different to avoid especially the federal-level bloat that’s taken place over the past hundred years or so. You can always go anarchist in response to this democratic mess: what did our old friend Lysander Spooner say? “But whether the Constitution really be one thing, or another, this much is certain – that it has either authorized such a government as we have had, or has been powerless to prevent it. In either case, it is unfit to exist.” This move is considered super radical, though, and may create more moral problems than it solves. So I dunno. I’ve recently been describing myself as “anarchist a few days per week,” but the whole thing is just very intellectually unsettling.

Problematically, since libertarians are already so often accused of being racists/classists/elitists/etc, they shy away from discussing sociocultural factors and their contributions to the failures of democracy at least as much as anyone else, because political correctness. You can’t talk about net tax payers versus net tax recipients because that breaks along race lines. You can’t talk about how some local and state governments, and their institutions like schools, work much better than others because of their underlying demographic homogeneity. So the minarchist-libertarian move is just to narrow the sphere of goodies and power over which the voters may fight to as little as possible, or nothing. This tactic is in some tension with premise (1) of reactionary thought, that right is right and chaos is to be avoided. On the one hand, libertarians want to free up the social and legal space of freedom within which individuals operate. On the other hand, they want to minimize the amount of power in the hands of the government. But as society destabilizes due to that social and legal freedom, the citizen-voters of even an initially minimal state will want more out of their government: more help, more stuff, anything to keep them from going off the rails of that socially unmoored roller coaster. Equilibrium at the libertarian minimal state seems unlikely to be achieved: possibly because democratic-bureaucratic government inherently tends to grab at more power, possibly because the citizens in such an unhinged society are eager to give it up, probably both.

So I don’t really have anything further to say about democracy and its alternatives for now, until I’ve read more NR stuff, which I understand is divided on this point between monarchists and those who would have governments run like corporations? The latter family of recommendations is more familiar to my libertarian self, as it is not dissimilar from the anarchist’s proposals of a switch (or perhaps a return, depending on how you understand history) to a system of polycentric legal order and voluntary protective agencies. I need to read more about this. It’s the weak spot in my understanding of reactionary thought for sure.

Ok, there you have it, a maybe sort of comprehensive account of where I stand on these 5 proposed premises of reactionary thought. Presently, I probably occupy some space at the useful periphery of the intellectual community: not a paradigmatic reactionary, but not a dedicated objector either. Although/because “libertarianism is retarded” is the premise which I have the most trouble in outright accepting, it seems likely that I’ll have the most to offer in thinking about libertarianism vis-a-vis the (neo)reaction. Also, as far as I can tell, the women of the neoreaction are mostly currently wives and mothers, so I may represent a different but productive perspective on the gender things (no PoMo – true is true, just that occupying different places in life can make different true points salient).

Anyways, welcome, thanks for your time and feedback if you have any, and stay tuned.

xo,

C-Dubs